The Teacher: Pythagoras

An in-depth look at how this great teacher has guided us for more than 2500 years and a reflection on the main speculations that have been made about him.

The impact of Pythagoras of Samos on Western civilisation has been remarkable, and this has been acknowledged by both those who admire his influence and those who are more sceptical.

His political and philosophical teachings influenced the thinking of most of the pre-Socratic philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, and through them, the whole of Western philosophy. Bertrand Russell has said of Pythagoras:

I do not know of any other man who has been as influential as he was in the sphere of thought. I say this because what appears as Platonism is, when analyzed, found to be in essence Pythagoreanism.1

The following assessment of Pythagoras is attributed to the philosopher Empedocles (c. 494 - c. 434 BC):

There was among them a man of surpassing knowledge, who possessed vast wealth of understanding, capable of all kinds of cunning acts; for when he exerted himself with all his understanding, easily did he see every one of all the things that are, in ten and even twenty human lives.2

Plato in The Republic has written that:

Pythagoras was especially revered for this [method of life]; his followers even now use the title Pythagorean Way of Life, and they have a shining place among the rest of men.3

Conventional historians admit that no authentic writings of Pythagoras have survived for public use and that almost nothing is known for certain about his life. The nineteenth-century scholar Eduard Zeller (1814-1908) noted that the further we get from the time of Pythagoras, the greater the number of sources, while the reliability of these sources decreases. The historian Walter Burkert (1931–2015) added to this approach that the early sources are also problematic and contradictory, partly due to their fragmentary nature, but the main difficulty is that they not only refer to different aspects of ancient Pythagoreanism, but also give different interpretations of these aspects. For some, the so-called Pythagorean question remains one of the most complicated in the history of early Greek science, philosophy and religion, and has every chance of being relegated to the category of insoluble problems4.

Fortunately for serious seekers, Swedish philosopher Henry T. Laurency has been able to present us the modern formulation of Pythagorean world view (hylozoics) in his The Philosopher’s Stone, which was first published in 1950. In 1961 The Knowledge of Reality was published, which includes an overview of the history of the knowledge and Western philosophy from a hylozoic viewpoint. H. T. Laurency’s works are published on www.laurency.com.

The founder and teacher of hylozoics

Pythagoras called his world view hylozoics (in Greek “hyle” means “matter”, and “zoe” means “life”) or spiritual materialism, which states as a basic axiom that matter is the necessary basis of all consciousness. He hereby cleared the antithesis of spirit and matter, explaining that “spirit” is the indestructible consciousness of the atoms. All matter has spirit, or consciousness. All worlds are spiritual worlds, lower and higher ones5.

Pythagoras explained that reality has three aspects which are indissolubly and inseparably united without confusion or transformation, that all three are indispensable for a correct conception of reality.

The trinity of existence is made up of:

the matter aspect

the motion aspect (the energy aspect)

the consciousness aspect

All matter is composed of primordial atoms which Pythagoras called monads – the smallest possible parts of primordial matter and the smallest firm points for individual consciousness. These monads are indestructible, because of which there cannot be any death, only disintegration of form. Once the monads’ potential consciousness has been roused to life, their consciousness development is continued through a series of natural kingdoms in ever higher worlds, until they attain the highest divine kingdom.

The cosmos consists of a series of atomic worlds of different degrees of density. There are seven series of seven cosmic material worlds, making 49 worlds in all (1–7, 8–14, 15–21, 22–28, 29–35, 36–42, 43–49). The seven lowest cosmic worlds (43–49) contain billions of solar systems. The lowest world (49) is the physical world.

Each lower atomic kind is formed out of the next higher one (2 out of 1, 3 out of 2, 4 out of 3, etc.). The lowest atomic kind (49) thus contains all the 48 higher kinds. When an atomic kind is dissolved, the next higher kind is obtained; out of the physical atom are obtained 49 atoms of atomic kind 48.

All higher worlds embrace and penetrate all lower worlds. The apprehension of reality (the logically absolute apprehension by consciousness of the aspects of reality) differs in the different worlds depending on differences in density of primordial atoms, resulting in differences in dimension, duration, material composition, motion, consciousness, and conformity to law.6

The meaning of existence is the consciousness development of the primordial atoms, to awaken to consciousness primordial atoms which are unconscious in primordial matter, and thereupon to teach them in ever higher kingdoms to acquire consciousness of life, understanding of life in all its relationships.

The goal of existence is the omniscience and omnipotence of all in the whole cosmos.

The process implies development: in respect of knowledge from ignorance to omniscience, in respect of will from impotence to omnipotence, in respect of freedom from bondage to that power which the application of the laws affords, in respect of life from isolation to unity with all life.

The self (monad’s consciousness) develops in and through envelopes, from the lowest physical etheric envelope to the highest cosmic world. It constantly acquires new envelopes in one world after another. Step by step it acquires self-consciousness in the ever higher molecular kinds of its envelope by learning to activate the consciousness in these. By this it finally becomes the master of its envelope. Until then it is disoriented in the consciousness chaos of this envelope, and it is the victim of vibrations from without.7

All the forms of nature are envelopes. In every atom, molecule, organism, world, planet, solar system, etc., there is one monad at a higher stage of development than are the other monads in that form of nature. All forms other than organisms are aggregate envelopes, which consist of molecules of the kinds of matter of the respective worlds held together electromagnetically. When incarnated in the physical world, man has five envelopes (or bodies), starting from the lowest:

an organism in the visible physical world (49:5-7)

an envelope of physical etheric matter (49:2-4)

an envelope of emotional matter (48:2-7)

an envelope of mental matter (47:4-7)

an envelope of causal matter (47:1-3)

The lower four of these are renewed at each new incarnation and are dissolved in their order at the end of the incarnation. The causal envelope is man’s one permanent envelope. It was acquired when the monad passed from the animal kingdom to the human kingdom. This causal envelope is the “true” man and incarnates together with the human monad which it always encloses.8

Some of the elements of the world-view taught by Pythagoras can be pieced together from exoteric sources that have come down to us through various other authors. But they are hopelessly scattered around, distorted and can only be recognised by reflecting on Pythagoras' teaching and precise terminology. For example, the neo-Platonic philosopher Porphyry (c. 234 – c. 305 AD) writes of Pythagoras many centuries later as follows:

What he said to his disciples no man can tell for certain, since they preserved such an exceptional silence. However, the following facts in particular became universally known: first that they held the soul to be immortal, next that it migrates into other kinds of animal, further that past events repeat themselves in a cyclic process and nothing is new in an absolute sense, and finally that one must regard all living things as kindred. These are the beliefs which Pythagoras is said to have been the first to introduce into Greece.9

Four insights can be recognized from the above mentioned text.

Firstly, hylozoics maintains that every individual as a monad (primordial atom) is immortal, because the monads are the sole indestructible material forms in the universe.

Secondly, there is rebirth of everything, meaning that all material forms (atoms, molecules, aggregates, worlds, planets, solar systems, aggregates of solar systems, etc.) are subject to the law of transformation. They are being formed, changed, dissolved, and re-formed.10

Thirdly, activity in existence occurs in ordered cycles and knowledge of periodicity or time-cycles is an important element for understanding more of the motion aspect.

And fourthly, all living beings are united in consciousness and form a unity, which should be discovered and embraced by every individual especially in the human kingdom.

The founder of an esoteric school of knowledge

The Hylozoic world view and life view was taught in the esoteric order of knowledge founded by Pythagoras in Sicily for those who were ready and worthy to receive such a comprehensive teaching.

The order had several degrees. Porphyry has stated that Pythagoras' teaching took at least two forms, and of his followers some were called mathematici and others acusmatici. The mathematici were those who had mastered the deepest and most fully elaborated parts of his wisdom, and the acusmatici those who had heard only summarised precepts from the writings without full explanation.11

But it is highly likely that there were more than two degrees in the Order. Iamblichus (c. 245 – c. 325 AD) has explained that Pythagoras established different grades among his disciples according to their natural talents, so that the highest secrets of his wisdom would be imparted only to those capable of receiving them.12 Iamblichus has also said that candidates for membership of the brotherhood were required by Pythagoras to observe five years of silence as part of their novitiate.13

To the members of this order was imparted, under vow of secrecy as in the original mysteries, the knowledge of reality, which ignorance will always distort and which the thirst for power will always abuse. In the lowest degree the knowledge was imparted in the form of myth. In the higher degrees increasingly more interpretations of the symbols were given. Some of these myths, which were also distorted, have become known to posterity.

The higher initiates were given knowledge of the existence of higher material worlds than the physical. Writing symbolically the Pythagoreans recorded their master’s doctrine of, among other matters, the three equivalent aspects of existence (matter, consciousness and motion). They taught that the meaning of life is the development of consciousness, that:

“consciousness sleeps in the stone, dreams in the plant, awakens in the animal, becomes self-consciousness in man, consciousness of unity in the fifth natural kingdom, and acquires omniscience embracing more and more in ever higher divine kingdoms”.14

What else they taught is partly hinted at in the works of the subsequent esoteric (so-called pre-Sokratic) philosophers.

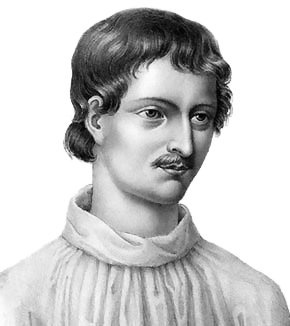

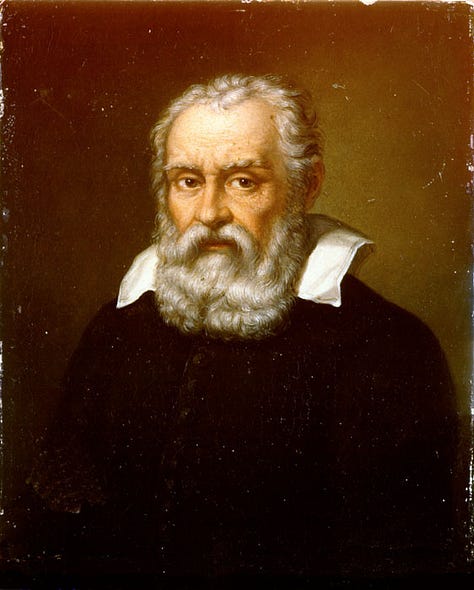

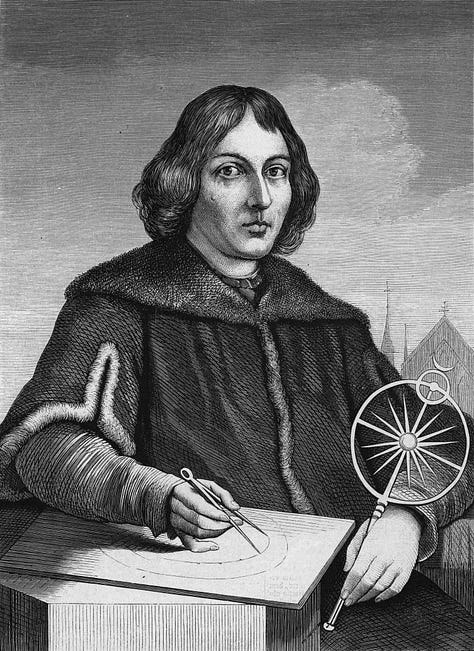

In the Middle Ages, Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Giordano Bruno, among others, had access to copies of these Pythagorean manuscripts.15

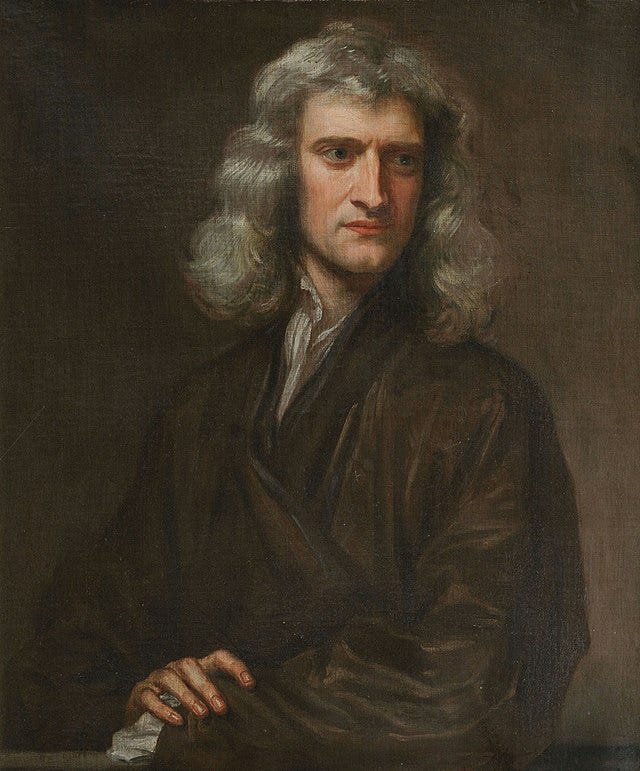

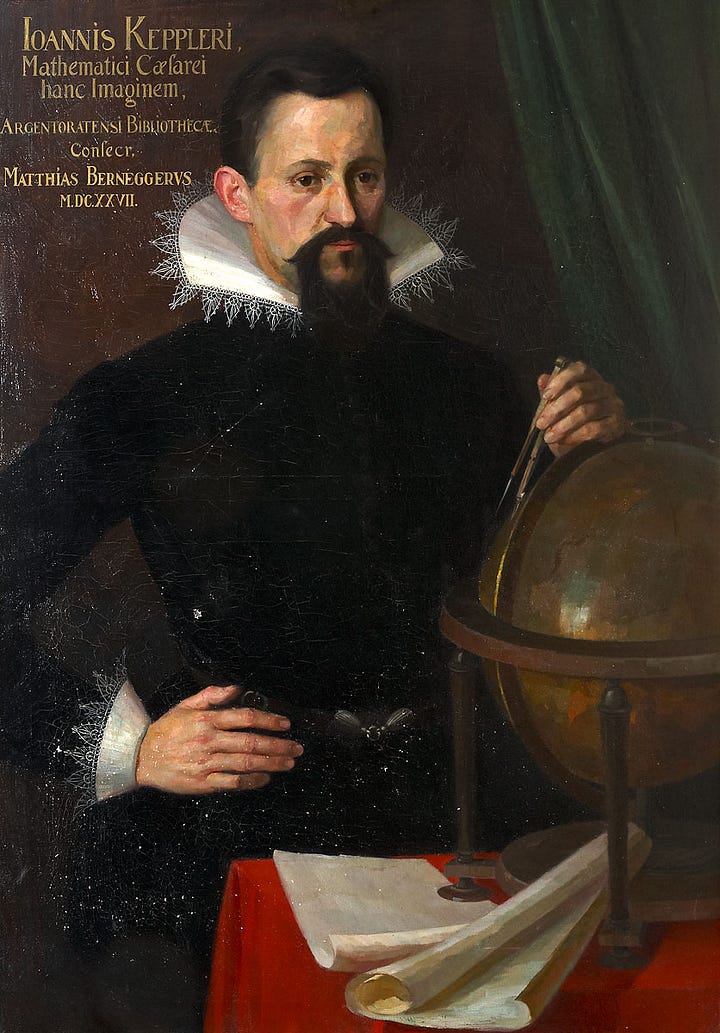

Pythagoras’ philosophy had a major impact on scientists such as Isaac Newton16 and also Johannes Kepler, who considered himself to be a Pythagorean.17

Pythagoras’ and the Pythagoreans participation in governance

The esoteric school of Pythagoras was not only a closed circle of worthy disciples, but he and his disciples paid close attention to the world around them and took part in governmental affairs wherever they were offered by the local people.

Dicaearchus (c. 345 - 295 BC) relates that when this impressive and much-travelled man arrived, his eloquence so won over the older and ruling citizens that they invited him to address the younger men, schoolchildren and women as well.

Diogenes (c. 410 - 323 BC) said that Pythagoras and his followers governed so well that they deserved the name of aristocracy (government of the best) in the literal sense.18

Probably the Pythagoreans participated in the governing of a number of southern Italian cities at least in the first half of the 5th century.19

The legendary second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius (753-672 BC; reigned 715-672 BC), is said to have been a pupil of Pythagoras.

The Roman historian Titus Livius (59 BC - 17 AD), in his Ab Urbe Condita ('From the Founding of the City'), has stated the following:

“Numa Pompilius’ master is given as Pythagoras of Samos, as tradition speaks of no other.”20

He then goes on to say that this statement is erronous because, as he comprehends it, it is generally agreed that Pythagoras was active more than a century later. But all historians have based their claims about Pythagoras' life, and even the century in which he lived, mainly on Aristoxenus (c. 375-335 BC), the pupil of Aristotle, who himself lived at least several hundred years after Pythagoras.

Falsehoods about Pythagoras

Pythagoras has been regarded by conventionalist historians as a philosopher, scientist and the first mathematician, but also the leader of a religious “sect”, who amongst other things allegedly believed in “transmigration of souls” (metempsychosis) and ordered his pupils to avoid “eating beans”.

Historians have made all sorts of claims about Pythagoras and have speculated on his life, his teaching and even contribute certain quotes to him. It is very likely that most things told about him is false, is far from the truth and this on the following grounds:

Firstly, Pythagoras was a highly developed being, an essential self (a 46-self)21 – an individual, who has an envelope and self-consciousness in the essential world of our planet (world 46 out of 49 worlds, world 49 being the lowest or the visible physical world). Such an individual has become a member of the fifth natural kingdom and is not a member of the fourth natural kingdom or humanity anymore. The essential self does not need to incarnate further, since he has no more to learn in the kingdom of man. He often does incarnate, however, in order by all means and by personal contact to help those preparing for their entrance into this higher kingdom. All the thanks he may reckon on are to be misunderstood, abused, and persecuted.22

Unfortunately it has become a rule during the last millennia that almost every highly evolved teacher of mankind has not been understood by his contemporaries or posterity and thus accounts on their lives and sayings are mostly ungrounded.

Secondly, Pythagoras was the founder of an esoteric knowledge order, which kept its knowledge and teaching strictly in secret and revealed it only to those worthy of it.

Greek rhetorician Isocrates (ca 436–338 BC) has remarked that:

“Those who claim to be disciples of Pythagoras are more admired for their silence than are the most famous orators for their speech.”7

Many speculations have been spread on Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans over the centuries. Not all the false claims and speculations about this great teacher will be refuted, as it is not essentially necessary for those serious seekers who are gaining a deeper interest in hylozoics and the Pythagorean way of life. Just four widespread falsehoods will be presently addressed:

Allegedly founded a religious sect and was mostly a religious leader

Walter Burkert (1972) and more recently e.g. Christoph Riedweg (2005) have been particularly laborious in working out various speculations about Pythagoras. They have claimed that the pre-Platonic tradition contains no evidence for the scientific or philosophical work of Pythagoras and his closest followers, and that Pythagoras thus appears as a religious teacher who preached a doctrine close to Orphism, on the transmigration of souls, and founded a secret sect in which his followers led a life governed by strict and absurd taboos.23

How unfounded and erroneous this view is has already been demonstrated earlier in this paper. However, it is important to add another aspect to Pythagoras' work and teaching that contributed to the development of a scientific and accurate understanding of reality.

Pythagoras realised that the Greeks had the prerequisites for comprehending objective reality, for scientific method, and for systematic thinking. Cultivating the consciousness aspect, as the Orientals do, before the foundation for understanding material reality has been laid, results in subjectivism and in a life of unbridled imagination. It is to Pythagoras that we owe most of our fundamental reality concepts, which today’s conceptual analysts (being ignorant of reality) are so busy trying to discard, thereby making a comprehension of reality definitively impossible. Pythagoras, with his doctrine of monads, and Demokritos, with his exoteric atomic theory, can be considered the first two scientists in the Western sense. They realised that the matter aspect is the necessary basis of a scientific approach. Without this basis, there will be no accuracy in exploring the nature of things and their relationships. There are no controllable limits to individual consciousness, but it has a tendency to drown in the ocean of consciousness.24

Allegedly believed in “transmigration of souls” (metempsychosis)

Transmigration of souls has been attributed to Pythagoras by a number of historians and researchers without knowing about the essence of Pythagoras’ teaching. An essential part of hylozoics is not transmigration, but reincarnation, the "rebirth" of everything. Man is reborn as a man (never as an animal), until he has learned everything he can learn in the human kingdom, and has acquired all the qualities and abilities necessary to enable him to continue his consciousness expansion in the next kingdom, the fifth natural kingdom. Rebirth explains both the seeming injustices of life (since in new lives the individual has to reap what he has sown in previous lives) and the innate, latent understanding and the once self-acquired abilities that exist as predispositions.25

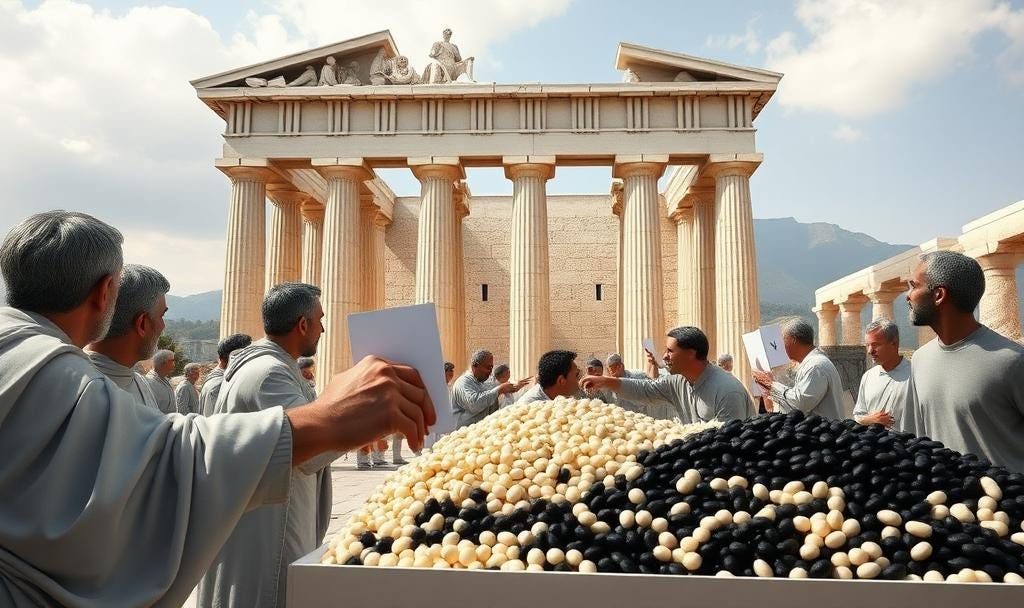

Allegedly avoided “beans”

"Keep away from beans" was a metaphorical suggestion used by the Pythagoreans to keep away from factional politics and political wrangling. Beans were used in some political procedures in ancient Greece, and in some places the voting system in Greece used white and black beans. So it has nothing to do with avoiding eating beans.

Allegedly founded a school in South Italian city Crotone (Calabria)

It is very likely that the few scarce historical sources, written hundreds of years after the appearance of Pythagoras and which form the basis of modern speculation about Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, have confused some terms concerning Pythagoras' activity in Italy. Pythagoras called his esoteric school Krotona, which he founded outside the town of Taormina in Sicily.26 Krotona has been misunderstood by posterity as Crotone (a city in southern Italy, in the province of Calabria), and this has been assumed to be the place of activity of the Pythagorean school of knowledge.

Bertrand Russel The History of Western Philosophy (1945), p 37

Ibid, p 161

Plato, The Republic, 600a-b

Leonid Shmud Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans (2012), p.1

Henry T. Laurency The Knowledge of Reality, 1.4.1

Ibid, 1.6.4, 1.4.5

Henry T. Laurency The Knowledge of Reality, 1.30.1, 1.30.4

Ibid, 1.13.2-1.14.2

W.K.C. Guthrie A History of Greek Philosophy: the earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans (1988), p 186

Henry T. Laurency The Knowledge of Reality, 1.31.1

W.K.C. Guthrie A History of Greek Philosophy: the earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans (1988), p 192

Ibid, p 191

Ibid, p 151

Henry T. Laurency The Knowledge of Reality, 5.4.1-5.4.4

Ibid, 5.4.7

Kitty Ferguson The Music of Pythagoras: How an Ancient Brotherhood Cracked the Code of the Universe and Lit the Path from Antiquity to Outer Space (2008), p 279

Ibid, p 265

W.K.C. Guthrie A History of Greek Philosophy: the earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans (1988), p 175

Ibid, p 175

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/From_the_Founding_of_the_City/Book_1#18

Henry T. Laurency The Knowledge of Reality, 5.4.1

Ibid, 1.35.12

Leonid Shmud Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans (2012), p 14

Henry T. Laurency The Knowledge of Reality, 1.4.8

Ibid, 1.31.4

Ibid, 5.4.1